This page has moved to ecsharp.net.

GitHub doesn't support HTTP redirects, so you'll be redirected via JavaScript in 5 seconds.LLLPG Part 2: Learning how to parse

26 Nov 2013 (updated 6 Mar 2016)Introduction

New to LLLPG? Start at part 1.

In this article series I will be teaching not just how to use my parser generator, but broader knowledge such as: what kinds of parser generators are out there? What’s ambiguity and what do we do about it? What’s a terminal? So in this article I’ll start with a general discussion of parsing terminology and parsing techniques, and then I will teach you about some useful core features of LLLPG.

Note: if you’re wondering how to configure LLLPG or how to structure your source code, visit part 3 (“Configuring LLLPG”, “Boilerplate”), then return here.

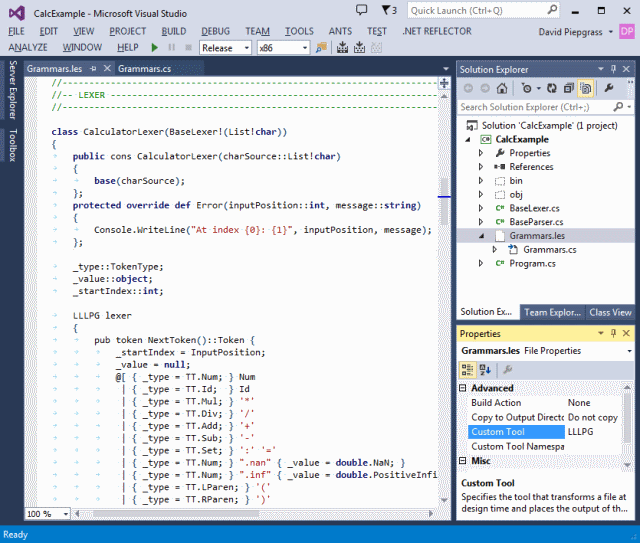

Note: The LES syntax highlighter works in Visual Studio 2010 through 2015. The Custom Tool works in VS 2008 through VS 2015, including Express editions, and if you’re wondering how it’s made, I wrote a whole article about that.

Note: In future articles you will see @[...] syntax for token literals instead of @{...}. @{...} is the new style, and @[...] is the old style. Both syntaxes are supported in EC#, but in LES, the @[...] syntax was replaced with @{...} as part of a change that made LES into a superset of JSON.

Do you really need a parser generator?

One of the most common introductory examples for any parser generator is an expression parser or calculator, like this calculator bundled with the previous article:

LLLPG parser(laType(int)) {

rule Atom()::double @[

{ result::double; }

( t:=id { result = Vars[t.Value -> string]; }

| t:=num { result = t.Value -> double; }

| '-' result=Atom { result = -result; }

| '(' result=Expr ')'

| error { result = 0;

Error(InputPosition, "Expected identifer, number, or (stuff)"); }

)

{ return result; }

];

rule MulExpr()::double @[

result:=Atom

(op:=(mul|div) rhs:=Atom { result = Do(result, op, rhs); })*

{ return result; }

];

rule AddExpr()::double @[

result:=MulExpr

(op:=(add|sub) rhs:=MulExpr { result = Do(result, op, rhs); })*

{ return result; }

];

rule Expr()::double @[

{ result::double; }

( t:=id set result=Expr { Vars[t.Value.ToString()] = result; }

| result=AddExpr )

{ return result; }

];

};

def Do(left::double, op::Token, right::double)::double

{

switch op.Type {

case add; return left + right;

case sub; return left - right;

case mul; return left * right;

case div; return left / right;

};

return double.NaN; };

But if expression parsing is all you need, you don’t really need a parser generator; there are simpler options for parsing, such as using a Pratt Parser like this one. If you only need to parse simple text fields like phone numbers, you can use regular expressions. And even if you need an entire programming language, you don’t necessarily need to create your own; for example you could re-use the LES parser included in Loyc.Syntax.dll, which comes with LLLPG (it’s not 100% complete yet, but it’s usable enough for LLLPG), and if you don’t re-use the parser you might still want to re-use the lexer.

So before you go writing a parser, especially if it’s for something important rather than “for fun”, seriously consider whether an existing parser would be good enough. Let me know if you have any questions about LES, Loyc trees, or using the Loyc libraries (Loyc.Essentials.dll, Loyc.Collections.dll, and so on).

Parsing terminology

I’ll start with a short glossary of standard parsing terminology.

First of all, grammars consist of terminals and nonterminals.

A terminal is an item from the input; when you are defining a lexer, a terminal is a single character, and when you are defining a parser, a terminal is a token from the lexer. More specifically, the grammar is concerned only with the type of the token, not its value. For example one of your token types might be Number, and a parser cannot treat a particular number specially; so if you ever need to treat the number “0” differently than other numbers, then your lexer would have to create a special token type for that number (e.g. Zero), because the grammar cannot make decisions based on a token’s value. Note: in LLLPG you can circumvent this rule if you need to, but it won’t be pretty.

A nonterminal is a rule in the grammar. So in this grammar:

token Spaces @[ (' '|'t')+ ];

token Id @[

('a'..'z'|'A'..'Z'|'_')

('a'..'z'|'A'..'Z'|'_'|'0'..'9')*

];

token Int @[ '0'..'9'+ ];

token Token @[ Spaces | Id | Int ];

The nonterminals are Spaces, Id, Int and Token, while the terminals are inputs like 's', 't', '9', and so forth.

Traditional literature about parsing assumes that there is a single “Start Rule” that represents the entire language. For example, if you want to parse C#, then the start rule would say something like “zero or more using statements, followed by zero or more namespaces and/or classes”:

rule Start @[ UsingStmt* TopLevelDecl* ];

rule TopLevelDecl @[ NamespaceStmt | TypeDecl ];

...

However, LLLPG is more flexible than that. It doesn’t limit you to one start rule; instead, LLLPG assumes you might start with any rule that isn’t marked private. After all, you might want to parse just a subset of the language, such as a method declaration, a single statement, or a single expression.

LLLPG rules express grammars in a somewhat non-standard way. Firstly, LLLPG notation is based on ANTLR notation, which itself is mildly different from EBNF (Extended Backus–Naur Form) notation which, in some circles, is considered more standard. Also, because LLLPG is embedded inside another programming language (LES or EC#), it uses the @[...] notation which means “token literal”. A token literal is a sequence of tokens that is not interpreted by the host language; the host language merely figures out the boundaries of the “token literal” and saves the tokens so that LLLPG can use them later. So while a rule in EBNF might look like this:

Atom = ['-'], (num | id);

the same rule in LLLPG looks like this:

rule Atom @[ ('-')? (num | id) ];

In EBNF, [Foo] means Foo is optional, while LLLPG uses Foo? to express the same idea. Some versions of EBNF use {Foo} to represent a list of zero or more Foos, while LLLPG uses Foo* for the same thing.

In LLLPG, like ANTLR, {...} represents a block of normal code (C#), so braces can’t also represent a list. In LLLPG 1.0 I decided to support a compromise between the ANTLR and EBNF styles: you are allowed to write [...]? or [...]* instead of (…)? or (…)*; the ? or * suffix is still required. Thus, square brackets indicate nullability–that the region in square brackets may not consume any input.

Alternatives and grouping work the same way in LLLPG and EBNF (e.g. (a | b)), although LLLPG also has the notation (a / b) which I’ll explain later.

In addition, some grammar representations do not allow loops, or even optional items. For example, formal “four-tuple” grammars are defined this way. I discuss this further in my blog post, Grammars: theory vs practice.

A “language” is a different concept than a “grammar”. A grammar represents some kind of language, but generally there are many possible grammars that could represent the same language. The word “language” refers to the set of sentences that are considered valid; two different grammars represent the same language if they accept or reject the same input (or, looking at the matter in reverse, if you can generate the same set of “sentences” from both grammars). For example, the following four rules all represent a list of digits:

rule Digits1 @[ '0'..'9'+ ];

rule Digits2 @[ '0'..'9'* '0'..'9' ];

rule Digits3 @[ '0'..'9' | Digits3 '0'..'9' ];

rule Digits4 @[ ('0'..'9'+)* ];

If we consider each rule to be a separate grammar, the four grammars all represent the same language (a list of digits). But the grammars are of different types: Digits1 is an LL(1) grammar, Digits2 is LL(2), Digits3 is LALR(1), and I don’t know what the heck to call Digits4 (it’s highly ambiguous, and weird). Since LLLPG is an LL(k) parser generator, it supports the first two grammars, but can’t handle the other two; it will print warnings about “ambiguity” for Digits3 and Digits4, then generate code that doesn’t work properly. Actually, while Digits4 is truly ambiguous, Digits3 is actually unambiguous. However, Digits3 is ambiguous “in LL(k)”, meaning that it is ambiguous from the LL(k) perspective (which is LLLPG’s perspective).

The word nullable means “can match nothing”. For example, @[ '0'..'9'* ] is nullable because it successfully “matches” an input like “hello, world” by doing nothing; but @[ '0'..'9'+ ] is not nullable, and will only match something that starts with at least one digit.

LL(k) versus the competition

LLLPG is in the LL(k) family of parser generators. It is suitable for writing both lexers (also known as tokenizers or scanners) and parsers, but not for writing one-stage parsers that combine lexing and parsing into one step. It is more powerful than LL(1) parser generators such as Coco/R.

LL(k) parsers, both generated and hand-written, are very popular. Personally, I like the LL(k) class of parsers because I find them intuitive, and they are intuitive because when you write a parser by hand, it is natural to end up with a mostly-LL(k) parser. But there are two other popular families of parser generators for computer languages, based on LALR(1) and PEGs:

- LALR(1) parsers are simplified LR(1) parsers which–well, it would take a lot of space to explain what LALR(1) is. Suffice it to say that LALR(1) parsers support left-recursion and use table-based lookups that are impractical to write by hand, i.e. a parser generator or similar infrastructure is always required, unlike LL(k) grammars which are straightforward to write by hand and therefore straightforward to understand. LALR(1) supports neither a superset nor a subset of LL(k) grammars; While I’m familiar with LALR(1), I admittedly don’t know anything about its more general cousin LR(k), and I am not aware of any parser generators for LR(k) or projects using LR(k). Regardless of merit, LR(k) for k>1 just isn’t very popular. I believe the main advantage of the LR family of parsers is that LR parsers support left- recursion while LL parsers do not (more on that later).

- PEGs are recursive-descent parsers with syntactic predicates, so PEG grammars are potentially very similar to grammars that you would use with LLLPG. However, PEG parsers traditionally do not use prediction (although prediction could probably be added as an optimization), which means that they don’t try to figure out in advance what the input means; for example, if the input is “42”, a PEG parser does not look at the ‘4’ and decide “oh, that looks like a number, so I’ll call the number sub-parser”. Instead, a PEG parser simply “tries out” each option starting with the first (is it spaces? is it an identifier?), until one of them successfully parses the input. Without a prediction step, PEG parsers apparently require memoization for efficiency (that is, a memory of failed and successful matches at each input character, to avoid repeating the same work over and over in different contexts). PEGs typically combine lexing (tokenization) and parsing into a single grammar (although it is not required), while other kinds of parsers separate lexing and parsing into independent stages.

Of course, I should also mention regular expressions, which probably the most popular parsing tool of all. However, while you can use regular expressions for simple parsing tasks, they are worthless for “full-scale” parsing, such as parsing an entire source file. The reason for this is that regular expressions do not support recursion; for example, the following rule is impossible to represent with a regular expression:

rule PairsOfParens @[ '(' PairsOfParens? ')' ];

Because of this limitation, I don’t think of regexes as a “serious” parsing tool.

Other kinds of parser generators also exist, but are less popular. Note that I’m only talking about parsers for computer languages; Natural Language Processing (e.g. to parse English) typically relies on different kinds of parsers that can handle ambiguity in more flexible ways. LLLPG is not really suitable for NLP.

As I was saying, the main difference between LL(k) and its closest cousin, the PEG, is that LL(k) parsers use prediction and LL(k) grammars usually suffer from ambiguity, while PEGs do not use prediction and the definition of PEGs pretends that ambiguity does not exist because it has a clearly-defined system of prioritization.

“Prediction” means figuring out which branch to take before it is taken. In a “plain” LL(k) parser (without and-predicates), the parser makes a decision and “never looks back”. For example, when parsing the following LL(1) grammar:

public rule Tokens @[ Token* ];

public rule Token @[ Float | Id | ' ' ];

token Float @[ '0'..'9'* '.' '0'..'9'+ ];

token Id @[ IdStart IdCont* ];

rule IdStart @[ 'a'..'z' | 'A'..'Z' | '_' ];

rule IdCont @[ IdStart | '0'..'9' ];

The Token method will get the next input character (known as LA0 or lookahead zero), check if it is a digit or ‘.’, and call Float if so or Id (or consume a space) otherwise. If the input is something like “42”, which does not match the definition of Float, the problem will be detected by the Float method, not by Token, and the parser cannot back up and try something else. If you add a new Int rule:

...

public rule Token @[ Float | Int | Id ];

token Float @[ '0'..'9'* '.' '0'..'9'+ ];

token Int @[ '0'..'9'+ ];

token Id @[ IdStart IdCont* ];

...

Now you have a problem, because the parser potentially requires infinite lookahead to distinguish between Float and Int. By default, LLLPG uses LL(2), meaning it allows at most two characters of lookahead. With two characters of lookahead, it is possible to tell that input like “1.5” is Float, but it is not possible to tell whether “42” is a Float or an Int without looking at the third character. Thus, this grammar is ambiguous in LL(2), even though it is unambiguous when you have infinite lookahead. The parser will handle single-digit integers fine, but given a two-digit integer it will call Float and then produce an error because the expected ‘.’ was missing.

A PEG parser does not have this problem; it will “try out” Float first and if that fails, the parser backs up and tries Int next. There’s a performance tradeoff, though, as the input will be scanned twice for the two rules.

Although LLLPG is designed to parse LL(k) grammars, it handles ambiguity similarly to a PEG: if A|B is ambiguous, the parser will choose A by default because it came first, but it will also warn you about the ambiguity.

Since the number of leading digits is unlimited, LLLPG will consider this grammar ambiguous no matter how high your maximum lookahead k (as in LL(k)) is. You can resolve the conflict by combining Float and Int into a single rule:

public rule Tokens @[ Token* ];

public rule Token @[ Number | Id ];

token Number @[ '.' '0'..'9'+

| '0'..'9'+ ('.' '0'..'9'+)? ];

token Id @[ IdStart IdCont* ];

...

Unfortunately, it’s a little tricky sometimes to merge rules correctly. In this case, the problem is that Int always starts with a digit but Float does not. My solution here was to separate out the case of “no leading digits” into a separate “alternative” from the “has leading digits” case. There are a few other solutions you could use, which I’ll discuss later in this article.

I mentioned that PEGs can combine lexing and parsing in a single grammar because they effectively support unlimited lookahead. To demonstrate why LL(k) parsers usually can’t combine lexing and parsing, imagine that you want to parse a program that supports variable assignments like x = 0 and function calls like x(0), something like this:

rule Expr @[ Assign | Call | ... ];

rule Assign @[ Id Equals Expr ];

rule Call @[ Id LParen ArgList ];

rule ArgList ...

...

If the input is received in the form of tokens, then this grammar only requires LL(2): the Expr parser just has to look at the second token to find out whether it is Equals (‘=’) or LParen (‘(‘) to decide whether to call Assign or Call. However, if the input is received in the form of characters, no amount of lookahead is enough! The input could be something like:

this_name_is_31_characters_long = 42;

To parse this directly from characters, 33 characters of lookahead would be required (LL(33)), and of course, in principle, there is no limit to the amount of lookahead. Besides, LLLPG is designed for small amounts of lookahead like LL(2) or maybe LL(4); a double-digit value is almost always a mistake. LL(33) could produce a ridiculously large and inefficient parser (I’m too afraid to even try it.)

In summary, LL(k) parsers are not as flexible as PEG parsers, because they are normally limited to k characters or tokens of lookahead, and k is usually small. PEGs, in contrast, can always “back up” and try another alternative when parsing fails. LLLPG makes up for this problem with “syntactic predicates”, which allow unlimited lookahead, but you must insert them yourself, so there is slightly more work involved and you have to pay some attention to the lookahead issue. In exchange for this extra effort, though, your parsers are likely to have better performance, because you are explicitly aware of when you are doing something expensive (large lookahead). I say “likely” because I haven’t been able to find any benchmarks comparing LL(k) parsers to PEG parsers, but I’ve heard rumors that PEGs are slower, and intuitively it seems to me that the memoization and retrying required by PEGs must have some cost, it can’t be free. Prediction is not free either, but since lookahead has a strict limit, the costs usually don’t get very high. Please note, however, that using syntactic predicates excessively could certainly cause an LLLPG parser to be slower than a PEG parser, especially given that LLLPG does not use memoization.

Let’s talk briefly about LL(k) versus LALR(1). Sadly, my memory of LALR(1) has faded since university, and while Googling around, I didn’t find any explanations of LALR(1) that I found really satisfying. Basically, LALR(1) is neither “better” nor “worse” than LL(k), it’s just different. As wikipedia says:

The LALR(k) parsers are incomparable with LL(k) parsers – for any j and k both greater than 0, there are LALR(j) grammars that are not LL(k) grammars and conversely. In fact, it is undecidable whether a given LL(1) grammar is LALR(k) for any k >= 0.

But I have a sense that most LALR parser generators in widespread use support only LALR(1), not LALR(k); thus, roughly speaking, LLLPG is more powerful than an LALR(1) parser generator because it can use multiple lookahead tokens. However, since LALR(k) and LL(k) are incompatible, you would have to alter an LALR(1) grammar to work in an LL(k) parser generator and vice versa.

Here are some key points about the three classes of parser generators.

LL(k):

- Straightforward to learn: just look at the generated code, you can see how it works directly.

- Straightforward to add custom behavior with action code (

{...}). - Straightforward default error handling. When unexpected input arrives, an LL(k) parser can always report what input it was expecting at the point of failure.

- Predictably good performance. Performance depends on how many lookahead characters are actually needed, not by the maximum k specified in the grammar definition. Performance of LL(k) parsers can be harmed by nesting rules too deeply, since each rule requires a method call (and often a prediction step); specifically, expression grammars often have this problem. But in LLLPG you can use a trick to handle large expression grammars without deep nesting (this is explained in Part 5.)

- LL(k) parser generators, including LLLPG, may support valuable extra features outside the realm of LL(k) grammars, such as zero-width assertions (a.k.a. and-predicates), and multiple techniques for dealing with ambiguity.

- No left recursion allowed (direct or indirect)

- Strictly limited lookahead. It’s easy to write grammars that require unlimited lookahead, so such grammars will have to be modified to work in LL(k). By the way, ANTLR overcomes this problem with techniques such as LL(*).

- Low memory requirements.

- Usually requires a separate parser and lexer.

LALR(1):

- Challenging to learn if you can’t find a good tutorial; the generated code may be impossible to follow

- Supports left recursion (direct and indirect)

- Some people feel that LALR(1) grammars are more elegant. For example, consider a rule “List” that represents a comma-separated list of numbers. The LALR(1) form of this rule would be

num | List ',' num, while the LL(1) form of the rule isnum (',' num)*. Which is better? You decide. - Low memory requirements.

- Usually requires a separate parser and lexer.

- LALR parser generators often have explicit mechanisms for specifying operator precedence.

PEGs:

- New! (formalized in 2004)

- Unlimited lookahead

- “No ambiguity” (wink, wink) - or rather, any ambiguity is simply ignored, “first rule wins”

- Supports zero-width assertions as a standard feature

- Grammars are composable. It is easier to merge different PEG parsers than different LL/LR parsers.

- Performance characteristics are not well-documented (as far as I’ve seen), but my intuition tells me to expect a naive memoization-based PEG parser generator to produce generally slow parsers. That said, I think all three parser types offer roughly O(N) performance to parse a file of size N.

- High memory requirements (due to memoization).

- It’s non-obvious how to support “custom actions”. Although a rule may parse successfully, its caller can fail (and often does), so I guess any work that a rule performs must be transactional, i.e. it must be possible to undo the action.

- Supports unified grammars: a parser and lexer in a single grammar.

Regexes:

- Very short, but often very cryptic, syntax.

- Matches characters directly; not usable for token-based parsing.

- Incapable of parsing languages of any significant size, because they do not support recursion or multiple “rules”.

- Most regex libraries have special shorthand directives like b that require significantly more code to express when using a parser generator.

- Regexes are traditionally interpreted, but may be compiled. Although regexes do a kind of parsing, regex engines are not called “parser generators” even if they generate code.

- Regexes are closely related to DFAs and NFAs.

Let me know if I missed anything.

Learning LLLPG, with numbers

So you still want to use LLLPG, even knowing about the competition? Phew, what a relief! Okay, let’s parse some numbers. Remember that code from earlier?

public rule Tokens @[ Token* ];

public rule Token @[ Float | Id | ' ' ];

token Float @[ '0'..'9'* '.' '0'..'9'+ ];

token Int @[ '0'..'9'+ ];

token Id @[ IdStart IdCont* ];

rule IdStart @[ 'a'..'z' | 'A'..'Z' | '_' ];

rule IdCont @[ IdStart | '0'..'9' ];

If you were hoping that I’d point out the difference between token and rule at this point… nope, I’m saving that for the next article. It’s not important yet; just use token for defining token rules (like Float, Int and Id) and you’ll be fine.

Now, since Float and Int are ambiguous in LL(k), here’s how I suggested combining them into a single rule:

token Number @[ '.' '0'..'9'+

| '0'..'9'+ ('.' '0'..'9'+)? ];

That’s arguably the cleanest solution, but there are others, and the alternatives are really useful for learning about LLLPG! First of all, one solution that looks simpler is this one:

token Number @[ '0'..'9'* ('.' '0'..'9'+)? ];

But now you’ll have a problem, because this matches an empty input, or it matches “hello” without consuming any input. Therefore, LLLPG will complain that Token is “nullable” and therefore must not be used in a loop (see Tokens). After all, if you call Number in a loop and it doesn’t match anything, you’ll have an infinite loop which is very bad.

Zero-width assertions: syntactic predicates

You can actually prevent it from matching an empty input as follows:

token Number @[ &('0'..'9'|'.')

'0'..'9'* ('.' '0'..'9'+)? ];

Here I have introduced the zero-width assertion or ZWA, also called an and-predicate because it uses the “and” sign (&). There are two kinds of and-predicates, which are called the “syntactic predicate” and the “semantic predicate”. This one is a syntactic predicate, which means that it tests for syntax, which means it tests a grammar fragment starting at the current position. And since it’s a zero-width assertion, it does not consuming any input (more precisely, it consumes input and then backtracks to the starting position, regardless of success or failure). and-predicates have two forms, the positive form & which checks that a condition is true, and the negative form &! which checks that a condition is false.

So, &('0'..'9'|'.') means that the number must start with '0'..'9' or '.'. Now Number() cannot possibly match an empty input. Unfortunately, LLLPG is not smart enough to know that it cannot match an empty input; it does not currently analyze and-predicates at all (it merely runs them), so it doesn’t understand the effect caused by &('0'..'9'|'.'). Consequently it will still complain that Token is nullable even though it isn’t. Hopefully this will be fixed in a future version, when I or some other smart cookie has time to figure out how to perform the analysis.

A syntactic predicate causes two methods to be generated to handle it:

private bool Try_Number_Test0(int lookaheadAmt)

{

using (new SavePosition(this, lookaheadAmt))

return Number_Test0();

}

private bool Number_Test0()

{

if (!TryMatchRange('.', '.', '0', '9'))

return false;

return true;

}

The first method assumes the existance of a data type called SavePosition (as usual, you can define it yourself or inherit it from a base class that I wrote.) SavePosition’s job is to:

- Save the current

InputPosition, and then restore that position whenDispose()is called - Increment

InputPositionbylookaheadAmt(which is often zero, but not always), where0 <= lookaheadAmt < k.

The Try_ method is used to start a syntactic predicate and then backtrack, regardless of whether the result was true or false. The second method decides whether the expected input is present at the current input position. Syntactic predicates also assume the existence of TryMatch and (for lexers) TryMatchRange methods, which must return true (and advance to the next the input position) if one of the expected characters (or tokens) is present, or false if not.

Here’s the code for Number() itself:

void Number()

{

int la0, la1;

Check(Try_Number_Test0(0), "[.0-9]");

for (;;) {

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 >= '0' && la0 <= '9')

Skip();

else

break;

}

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == '.') {

la1 = LA(1);

if (la1 >= '0' && la1 <= '9') {

Skip();

Skip();

for (;;) {

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 >= '0' && la0 <= '9')

Skip();

else

break;

}

}

}

}

Check()’s job is to print an error if the ZWA is not matched. If the Number rule is marked private, and the rule(s) that call Number() have already verified that Try_Number_Test0 is true, then for efficiency, the call to Check() will be eliminated by prematch analysis (mentioned in part 1).

Zero-width assertions: semantic predicates

Moving on now, another approach is:

token Number @[ {bool dot=false;}

('.' {dot=true;})?

'0'..'9'+ (&{!dot} '.' '0'..'9'+)?

];

Here I use the other kind of ZWA, the semantic predicate, to test whether dot is false (&{!dot}, which can be written equivalently as &!{dot}). &{expr} simply specifies a condition that must be true in order to proceed; it is normally used to resolve ambiguity between two possible paths through the grammar. Semantic predicates are a distinctly simpler feature than syntactic predicates and were implemented first in LLLPG. They simply test the user-defined expression during prediction.

So, here I have created a “dot” flag which is set to “true” if the first character is a dot. The sequence '.' '0'..'9'+ is only allowed if the “dot” flag has not been set. This approach works correctly; however, you must exercise caution when using &{...} because &{...} blocks may execute earlier than you might expect them to; this is explained below.

Here’s the code generated for this version of Number:

void Number()

{

int la0, la1;

bool dot = false;

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == '.') {

Skip();

dot = true;

}

MatchRange('0', '9');

for (;;) {

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 >= '0' && la0 <= '9')

Skip();

else

break;

}

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == '.') {

if (!dot) {

la1 = LA(1);

if (la1 >= '0' && la1 <= '9') {

Skip();

Skip();

for (;;) {

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 >= '0' && la0 <= '9')

Skip();

else

break;

}

}

}

}

}

The expression inside &{...} can include the “substitution variables” $LI and $LA, which refer to the current lookahead index and the current lookahead value; these are useful if you want to run a test on the input character. For example, when if you want to detect letters, you might write:

rule Letter @[ 'a'..'z' | 'A'..'Z' ];

token Word @[ Letter+ ];

but this doesn’t detect all possible letters; there are áĉçèntéd letters to worry about, grΣεk letters, Russiaи letters and so on. I’ve been supporting these other letters with a semantic and-predicate:

rule Letter @[ 'a'..'z' | 'A'..'Z'| &{char.IsLetter((char) $LA)} 0x80..0xFFFC ];

[FullLLk] token Word @[ Letter+ ];

0x80..0xFFFC denotes all the non-ASCII characters supported by a .NET char, while the arrow operator -> is the LeMP/LES notation for a cast; the C# equivalent is char.IsLetter((char) $LA). $LA will be replaced with the appropriate lookahead token, which is most often LA0, but not always. Now, when you look at the generated code, you’ll notice that the and-predicate has been copied into the Word rule:

void Word()

{

int la0;

Letter();

for (;;) {

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 >= 'A' && la0 <= 'Z' || la0 >= 'a' && la0 <= 'z')

Letter();

else if (la0 >= 128 && la0 <= 65532) {

la0 = LA0;

if (char.IsLetter((char) la0))

Letter();

else

break;

} else

break;

}

}

Copying and-predicates across rules is normal behavior that occurs whenever one rule needs to use the and-predicate to decide whether to call another rule. ANTLR calls this “hoisting”, so that’s what I call it too: the predicate was hoisted from Letter to Word. (In this particular case I had to add FullLLk to make it work this way; more about that in a future article.)

While writing the EC# parser, I noticed that hoisting is bad when local variables are involved, since a function obviously can’t refer to a local variable of another method. For example, the predicate in the earlier Number example should not be hoisted. To ensure that it is not copied between rules, you can add the [Local] attribute inside the braces:

token Number @[ {bool dot=false;}

('.' {dot=true;})?

'0'..'9'+ (&{[Local] !dot} '.' '0'..'9'+)?

];

Note: Currently the [Local] flag is implemented only for &{semantic} predicates, not &(syntactic) predicates.

Gates

Here’s one final technique:

token Number @[ '.'? '0'..'9' =>

'0'..'9'* ('.' '0'..'9'+)? ];

This example introduces a feature that I call “the gate”. The grammar fragment ('.'? '0'..'9'+) before the gate operator => is not actually used by Number itself, but it can be used by the caller to decide whether to invoke the rule.

A gate is an advanced but simple mechanism to alter the way prediction works. Recall that parsing is a series of prediction and matching steps. First the parser decides what path to take next, which is called “prediction”, then it matches based on that decision. Normally, prediction and matching are based on the same information. However, a gate => causes different information to be given to prediction and matching. The left-hand side of the gate is used for the purpose of prediction analysis; the right-hand side is used for matching.

The decision of whether or not Token will call the Number rule is a prediction decision, therefore it uses the left-hand side of the gate. This ensures that the caller will not believe that Number can match an empty input. When code is generated for Number itself, the left-hand side of the gate is ignored because it is not part of an “alts” (i.e. the gate expression is not located in a loop or within a list of alternatives separated by |, so no prediction decision is needed). Instead, Number just runs the matching code, which is the right-hand side, '0'..'9'* ('.' '0'..'9'+)?.

Gates are a way of lying to the prediction system. You are telling it to expect a certain pattern, then saying “no, no, match this other pattern instead.” Gates are rarely needed, but they can provide simple solutions to certain tricky problems.

Here’s the code generated for Number, but note that '0'..'9'* ('.' '0'..'9'+)? (without the gate) would produce exactly the same code.

void Number()

{

int la0, la1;

for (;;) {

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 >= '0' && la0 <= '9')

Skip();

else

break;

}

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == '.') {

la1 = LA(1);

if (la1 >= '0' && la1 <= '9') {

Skip();

Skip();

for (;;) {

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 >= '0' && la0 <= '9')

Skip();

else

break;

}

}

}

}

Gates can also be used to produce nonsensical code, e.g.

// 'A' => 'Q'

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == 'A')

Match('Q');

But don’t do that.

Please note that gates, unlike syntactic predicates, do not provide unlimited lookahead. For example, if k=2, the characters 'c' 'd' in ('a' 'b' 'c' 'd' => ...) will not have any effect.

The gate operator => has higher precedence than |, so a | b => c | d is parsed as a | (b => c) | d.

One more thing, hardly worth mentioning. There are actually two gate operators: the normal one =>, and the “equivalence gate” <=>. The difference between them is the follow set assigned to the left-hand side of the gate. A normal gate => has a “false” follow set of _* (anything), and ambiguity warnings that involve this follow set are suppressed (the follow set of the right hand side is computed normally, e.g. in (('a' => A) 'b') the follow set of A is 'b'). The “equivalence gate” <=> tells LLLPG not to replace the follow set on the left-hand side, so that both sides have the same follow set. It only makes sense to use the equivalence gate if

- the left-hand side and right-hand side always have the same length,

- both sides are short, so that the follow set of the gate expression

P => Mcan affect prediction decisions. So far, I have never needed one.

More about and-predicates

Let’s see now, I was saying something about and-predicates running earlier than you might expect. Consider this example:

flag::bool = false;

public rule Paradox @[ {flag = true;} &{flag} 'x' / 'x' ];

Here I’ve introduced the “/” operator. It behaves identically to the “|” operator, but has the effect of suppressing warnings about ambiguity between the two branches (both branches match 'x' if flag == true, so they are certainly ambiguous).

What will the value of flag be after you call Paradox()? Since both branches are the same ('x'), the only way LLLPG can make a decision is by testing the and-predicate &{flag}. But the actions {flag=false;} and {flag=true;} execute after prediction, so &{flag} actually runs first even though it appears to come after {flag=true;}. You can clearly see this when you look at the actual generated code:

bool flag = false;

public void Paradox()

{

if (flag) {

flag = true;

Match('x');

} else

Match('x');

}

What happened here? Well, LLLPG doesn’t bother to read LA0 at all, because it won’t help make a decision. So the usual prediction step is replaced with a test of the and-predicate &{flag}, and then the matching code runs ({flag = true;} 'x' for the left branch and 'x' for the right branch).

This example will give the following warning: “It’s poor style to put a code block {} before an and-predicate &{} because the and-predicate normally runs first.”

In a different sense, though, and-predicates might run after you might expect. Let’s look again at the code for this Number rule from earlier:

token Number @[ {dot::bool=false;}

('.' {dot=true;})?

'0'..'9'+ (&{!dot} '.' '0'..'9'+)?

];

The generated code for this rule is:

void Number()

{

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == '.') {

if (!dot) {

la1 = LA(1);

if (la1 >= '0' && la1 <= '9') {

Skip();

Skip();

for (;;) {

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 >= '0' && la0 <= '9')

Skip();

else

break;

}

}

}

}

}

Here I would draw your attention to the way that (&{!dot} '.' '0'..'9'+)? is handled: first LLLPG checks if (la0 == '.'), then if (!dot) afterward, even though &{!dot} is written first in the grammar. Another example shows more specifically how LLLPG behaves:

token Foo @[ (&{a()} 'A' &{b()} 'B')? ];

void Foo()

{

int la0, la1;

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == 'A') {

if (a()) {

la1 = LA(1);

if (la1 == 'B') {

if (b()) {

Skip();

Skip();

}

}

}

}

}

First LLLPG tests for 'A', then it checks &{a()}, then it tests for 'B', and finally it checks &{b()}; it is as if the and-predicates are being “bumped” one position to the right. Actually, I decided that all zero-width assertions should work this way for the sake of performance. To understand this, consider the Letter and Word rules from earlier:

rule Letter @[ 'a'..'z' | 'A'..'Z'| &{char.IsLetter($LA -> char)} 0x80..0xFFFC ];

[FullLLk] token Word @[ Letter+ ];

In the code for Word you can see that char.IsLetter is called after the tests on LA0:

if (la0 >= 'A' && la0 <= 'Z' || la0 >= 'a' && la0 <= 'z')

Letter();

else if (la0 >= 128 && la0 <= 65532) {

la0 = LA0;

if (char.IsLetter((char) la0))

Letter();

else

break;

} else

break;

And this makes sense; if char.IsLetter were called first, there would be little point in testing for 'a'..'z' | 'A'..'Z' at all. It makes even more sense in the larger context of a “Token” rule like this one:

[FullLLk] rule Token @[ Spaces / Word / Number / Punctuation / Comma / _ ];

The Token method will look something like this (some newlines removed for brevity):

void Token()

{

int la0, la1;

la0 = LA0;

switch (la0) {

case 't': case ' ':

Spaces();

break;

case '.':

{

la1 = LA(1);

if (la1 >= '0' && la1 <= '9')

Number();

else

Punctuation();

}

break;

case '0': case '1': case '2': case '3': case '4':

case '5': case '6': case '7': case '8': case '9':

Number();

break;

case '!': case '#': case '$': case '%': case '&':

case '*': case '+': case ',': case '-': case '/':

case '<': case '=': case '>': case '?': case '@':

case '\': case '^': case '|':

Punctuation();

break;

default:

if (la0 >= 'A' && la0 <= 'Z' || la0 >= 'a' && la0 <= 'z')

Word();

else if (la0 >= 128 && la0 <= 65532) {

la0 = LA0;

if (char.IsLetter((char) la0))

Word();

else

MatchExcept();

} else

MatchExcept();

break;

}

}

In this example, clearly it makes more sense to examine LA0 before checking &{char.IsLetter(...)}. If LLLPG invoked the and-predicate first, the code would have the form:

void Token()

{

int la0, la1;

la0 = LA0;

if (char.IsLetter((char) la0)) {

switch (la0) {

}

} else {

switch (la0) {

}

}

}

The code of Token would be much longer, and slower too, since we’d call char.IsLetter on every single input character, not just the ones in the Unicode range 0x80..0xFFFC. Clearly, then, as a general rule it’s good that LLLPG tests the character values before the ZWAs.

In fact, I am now questioning whether the tests should be interleaved. As you’ve seen, it currently will test the character/token at position 0, then ZWAs at position 0, then the character/token at position 1, then ZWAs at position 1. This seemed like the best approach when I started, but in the EC# parser this ordering produces a Stmt (statement) method that is 3122 lines long (the original rule is just 58 lines), which is nearly half the LOCs of the entire parser; it looks like testing LA(0) and LA(1) before any ZWAs might work better, for that particular rule anyway.

Underscore and tilde

The underscore _ means “match any terminal”, while ~(X|Y) means “match any terminal except X or Y”. The next section has an example that uses both.

In ~(X|Y), X and Y must be terminals (if X and/or Y are non-terminals, consider using something like &!(X|Y) _ instead.)

A subtle point about ~(...) and _ is that both of them exclude EOF (-1 in a lexer). Thus ~X really means “anything except X or EOF”; and ~(~EOF) does not represent EOF, it represents the empty set (which, as far as I know, is completely useless). By the way, ~ causes LLLPG to use the MatchExcept() API which LLLPG assumes will not match EOF. So for ~(X|Y), LLLPG generates MatchExcept(X, Y) which must be equivalent to MatchExcept(X, Y, EOF).

Setting lookahead

Pure LL(k) parsers look up to k terminals ahead to make a branching decision, and once a decision is make they stick to it, they don’t “backtrack” or try something else. So if k is too low, LLLPG will generate code that makes incorrect decisions.

LLLPG’s default k value is 2, which is enough in the majority of situations, as long as your grammar is designed to be LL(k). To increase k to X, simply add a [DefaultK(X)] attribute to the grammar (i.e. the LLLPG statement), or add a [k(X)] attribute to a single rule ([LL(X)]is a synonym). Here’s an example that represents "double-quoted" and """triple-quoted""" strings, where k=2 is not enough:

private token DQString @[

'"' ('\' _ | ~('"'|'\'|'r'|'n'))* '"'? ];

];

[k(4)]

private token TQString @[

'"' '"' '"' nongreedy(Newline / _)* '"' '"' '"'

"'''" nongreedy(Newline / _)* "'''"

];

[k(4)]

private token Token @[

( {_type = TT.Spaces;} Spaces

...

| {_type = TT.String;} TQString

| {_type = TT.String;} DQString

...

)

];

Here I’ve used “_” inside both kinds of strings, meaning “match any character”, but this implies that the string can go on and on forever. To fix that, I add nongreedy meaning “exit the loop when it makes sense to do so” (greedy and nongreedy are explained more in my blog.)

With only two characters of lookahead, LLLPG cannot tell whether """this""" is an empty DQString ("") or a triple-quoted TQString. Since TQString is listed first, LLLPG will always choose TQString when a Token starts with "", but of course this may be the wrong decision. You’ll also get a warning like this one:

warning : Loyc.LLParserGenerator.Macros.run_LLLPG:

Alternatives (4, 5) are ambiguous for input such as «""» (["], ["])

[k(3)] is sufficient in this case, but it’s okay if you use a number that is a little higher than necessary, so I’ve used [k(4)] here.

LLLPG is not the Ferrari of parser generators.

During my experiences writing EC#, I’ve discovered that LLLPG can take virtually unlimited time and memory to process certain grammars (especially highly ambiguous grammars, such as the kind you will write accidentally during development), and processing time can increase exponentially with k. In fact, even at the default LL(2), certain complex grammars can make LLLPG run a very long time and use a large amount of RAM. At LL(3), the same “bad grammars” will make it run pretty much forever at LL(3) and suck up all your RAM. As I was writing my EC# parser under LLLPG 0.92, I made a seemingly innocuous change that caused it to take pretty much forever to process my grammar, even at LL(2).

The problem was hard to track down because it only seemed to happen in large, complex grammars, but eventually I figured out how to write a short grammar that made LLLPG sweat:

[DefaultK(2)] [FullLLk(false)]

LLLPG lexer {

rule PositiveDigit @[ '1'..'9' {""Think positive!""} ];

rule WeirdDigit @[ '0' | &{a} '1' | &{b} '2' | &{c} '3'

| &{d} '4' | &{e} '5' | &{f} '6' | &{g} '7'

| &{h} '8' | &{i} '9' ];

rule Start @[ (WeirdDigit / PositiveDigit)* ];

}

Originally LLLPG took about 15 seconds to process this, but I was able to fix it; now LLLPG can process this grammar with no perceptible delay. However, I realized that there was a similar grammar that the fix wouldn’t fix at all:

[DefaultK(2)] [FullLLk(false)]

LLLPG lexer {

rule PositiveDigit @[ '1'..'9' {""Think positive!""} ];

rule WeirdDigit @[ '0' | &{a} '1' | &{b} '2' | &{c} '3'

| &{d} '4' | &{e} '5' | &{f} '6' | &{g} '7'

| &{h} '8' | &{i} '9' ];

rule Start @[ WeirdDigit+ / PositiveDigit+ ];

}

Again, this takes about 15 seconds at LL(2) and virtually unlimited time at LL(3), and it looks like major design changes will be needed to overcome the problem.

Luckily, most grammars don’t make LLLPG horribly slow, but it’s no speed demon either. On my laptop, LLLPG processes the EC# lexer and parser in about 3 seconds each.

So, until I find time to fix the speed issue, I’d suggest using LL(2), which is the default, except in specific rules where you need more. In any case, large values of DefaultK will never be a good idea; I heard that in theory, for certain “hard” or highly ambiguous grammars, the output code size can grow exponentially as k increases (although I do not have any examples).

Wrapping Up

By now we’ve covered all the basic features. Ready for part 3? Then click the link!

In future articles I’ll talk more about the following topics.

tokenversusrule.- The API that LLLPG uses

- Saving inputs

- Managing ambiguity

- Error handling

- [**FullLLk] versus “approximate” LL(k)**

- My favorite feature that LLLPG doesn’t have: length-based disambiguation.

- A real-life example: parsing LES, or other stuff. Of course, the sample code included with this article is almost a real-life example already. Other parsing suggestions welcome.

- How-to: “tree parsing”: how to use LLLPG with three-stage parsing, where you group tokens by parenthesis and braces before the main parsing stage.

- How-to: keyword parsing: LLLPG can handle keywords directly, although the generated code is rather large.

- How LLLPG works: a brief tour of the source code? then again, I think no one cares that much.

- All about Loyc and its libraries.

- Things you can do with LeMP: other source code manipulators besides LLLPG.

- Do you want LLLPG to support a language other than C#? Let me know which language. Better yet, ask me how to write a new output module, and I’ll write a whole article just about that.

I would also love to hear how you’re planning to use LLLPG in your own projects. And don’t forget to share this article with your compiler-writing friends and university professors! (Dude, your friends write compilers? I seriously wish I had friends like yours.)

History

See part 1 for history.