Better floating point: posits in plain language

All about fractional numbers inside a computer 15 Dec 2019Welcoming all unums!

I first heard about the unum (universal number) format in relation to a book with a tantalizing name: “The End of Error”.

The idea was to get an accurate picture of the result of any given numeric calculation. It involved a variable-size number format that would sometimes be enlarged during calculations to an extent necessary to accurately describe a range (or set of ranges) of values in which the correct answer to a computation on real numbers might lie.

The details are complicated, but the result is awesome: the unum can tell you how much “rounding error” has happened, and it can give you a (usually) tightly-bounded range of values in which the mathematically perfect answer must lie. And if you need more accuracy, you can always get more in exchange for slower computations. In science, and sometimes engineering, you want to make sure you don’t get bad answers because of rounding errors you can’t quantify, so unums can sometimes offer big benefits, or at least let you sleep a little better knowing your calculation doesn’t suffer from a huge rounding error. However, the original unum was a variable-size format with multiple variable-size parts, and it would be challenging to work with those numbers efficiently, whether it be in software or in hardware.

But the author, John Gustafson, didn’t stop there - he went on to develop another version of the idea called “type-II unums”, which was elegant but required potentially huge lookup tables to implement in practice, and then “type-III unums” which I’ll teach you about today.

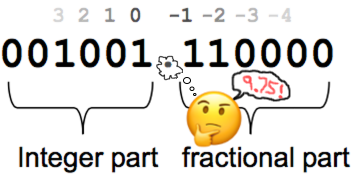

Fixed point

Are you familiar with the traditional floating point format? If you want to know about posits, it helps to understand that first. Don’t worry, I’ll teach you. But I’ll assume you understand the basics of binary. For example, you should be able to see that binary 1001 = 8+1 = 9, and you should be able to see that binary 10.01 is one-quarter of 1001 (2.25).

So, you know how you can express the number one as 1.0, or 01.00, or 000001.000000? Okay, so imagine we’re doing this in binary. For example:

- 000010.000000 is 2

- 000010.010000 is 2.25

- 000010.100000 is 2.5

- 001010.110000 is 10.75

- 000000.010011 is 19/64 which is approximately 0.3

Since computers only have zeros and ones, not minus signs or decimal points, we need some kind of trick to represent a number like “-11.01” (-3.25) that contains a “minus sign” and a “point”.

The minus sign is kind of easy. We just reserve one bit on the left side and call it the “sign bit”. But let’s stay positive and ignore those negative-nancy numbers for now.

The simplest way to represent the “point” is to simply imagine that there is a point in a fixed location, usually in the middle. In these examples there are always 12 bits and the point is always in the middle, so we can simply imagine the point is there and keep it in our minds as we design our software. This trick works well on simple computers that don’t support fractions at all.

So if we want to put the number 2.25 into the computer’s memory, we actually put the number 144 into memory instead (10010000) and then imagine a point (10.010000). If we want to put 3 into our computer, that’s 11 in binary, so, imagining a point, we put 11.000000 (192) into the computer’s memory. What we’re actually doing is multiplying everything by 64 (which is the same as a left-shift by 6 bits).

If the point is always in the same place, it’s called a “fixed point” number format. What if we want to multiply 2.25 by 3? Well, in memory what we stored was 2.25×64 and 3×64. If we multiply those numbers we get 144×192 = 2.25×64×3×64, but all of our numbers are supposed to be multiplied by 64 once, not twice. Therefore, after multiplying, you must divide by 64 (shift right by 6 bits) to get the correct result: 144×192/64 = 432, which is 110110000 in binary, which means 110.110000, which is 6.75, which is 2.25×3. Success!

I actually wrote commercial navigation software called “FastNav” that can draw a map in 3D, and I did it mostly with fixed-point math, because it’s the fastest way to do math in an old computer without a floating-point unit (I used C++ templates so that they were as easy to use as floating-point numbers, but that’s another story).

There’s a big problem with fixed point, though: really big or small numbers won’t fit, so your code must be very carefully designed to make sure that you never, ever need really big or small numbers, like, not even once, ever. This can be hard! If a really big or small number comes along, the calculations go bonkers and give terrible results. I mean, imagine multiplying 0.004 times 0.001 and getting zero as the answer. Or imagine multiplying 7000 times 10 and getting 4464 because an overflow occurred and you are using a stupid programming language like C++ that cannot inform you when an overflow has occurred, so you trust the answer and you end up drawing garbage on the screen. Thanks again C++… thanks a lot.

Traditional floating point

As you’ve probably heard, computers use floating point numbers to handle numbers that have a fractional part, like 5.125 or 0.07. Here’s how it works.

In any binary number (except zero), there’s a location where the first 1 appears. For example, the number 5.125 is 000101.001000 in binary, and the first “1” appears in the third slot to the left of the point.

The number 0.07 is approximately 0.00010001111011 in binary, and the first “1” appears in the fourth slot to the right of the point. I hope 0.07 is your lucky number, double-oh-seven, because I plan to use it a lot.

Imagine that in our computer there are 32 places where the first 1 is allowed to appear, numbered from 0 to 31 so that the first slot to the left of the decimal point is 15 or higher. Then we can say that the number 0.07 has its first “1” in slot 11:

0 0 0 .... 0 0 0 0 0 0. 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0

31 30 29 .... 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

This is the basic idea of floating point. We can’t store the point itself inside a computer, but we can store a number in the computer that represents the location of the first “1”, and then we know where the point is in relation to the number. In this case, we will store the number eleven (1011 in binary) in our computer to represent the location where the first “1” appears. And then we can store a bunch of digits that appear after the first “1”. In this case I’ve written eleven bits after the first “1”, and those eleven bits are 00011110110. Finally, remember the sign bit? Our number is positive, and here on Earth, humans have decided to use 0 to represent positive numbers.

If we’ve decided that we want our floating-point numbers to have a size of 16 bits, a reasonable choice is to use 1 sign bit, 5 bits for the location of the first “1”, and ten bits of precision. In that case, we can represent 0.07 as 0 01011 0001111011:

Sign

| First-1 Location

| ||||||||| Digits after the first "1"

| ||||||||| |||||||||||||||||||

0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1

Notice that the first “1” does not actually exist inside the computer; instead we just store the location where the first “1” appears. Actually storing that number “1” is not needed because we can just imagine its existence (based on the location we were given), just like we imagined the fixed point earlier. I guess floating-point computer hardware is designed by people who are able to imagine the hidden “1” correctly, or have a math degree, or something.

Let’s do another example: the number 5.125, which is 000101.001000 in binary. The first “1” is located in slot 17, and 17 is 10001 in binary, so we can store 5.125 in the computer like this:

Sign

| First-1 Location

| ||||||||| Digits after the first "1"

| ||||||||| |||||||||||||||||||

0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0

Now let’s try doing this in reverse: if we see the bit pattern 0 10001 0100100000, how do we figure out that it means 5.125? Well, the sign bit is 0, so we know the number is positive. Next, we see 10001 = 16 + 1 = 17, so we know that the first “1” appears in slot 17:

0 0 0 .... 0 0 0 1 ? ?. ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

31 30 29 .... 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

Next, we insert those last 10 bits, 0100100000, after the first one:

0 0 0 .... 0 0 0 1 0 1. 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

31 30 29 .... 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

Now we can see that the number is 101.001 binary, which is 4 + 1 + 1/8 = 5.125.

The number 0 is a special case because it doesn’t contain a “first 1” anywhere, so we need a special rule that if all the bits are zero (ignoring the sign bit), it means zero.

This 16-bit format is called “half-precision floating point”. It’s the smallest practical size for a floating-point number, and it became an official IEEE standard in 2008. The technical term for the “first-1 location” is “Exponent”, and the technical term for “Digits after the first 1” is “mantissa” or “significand”. Computers often use half-precision for numbers that represent pixels or sound waves in high-quality HDR image and sound files.

There’s a formula that explains how to convert from a half-precision floating-point bit pattern back to an ordinary “real” number. Let’s call the sign bit s, call the exponent e, and call the other 10 bits f (f = fraction). Also, let’s say ^ means “exponent operator” (e.g. 5^2 = 25). Here’s the formula:

(-1)^s × 2^(e-15) × (1 + f/(2^10))

For example, if b=0, e=01011 (which is 11), and f=0001111011 (which is 123), we plug those numbers into the formula and we get back to where we started, 0.07 (approximately):

(-1)^0 × 2^(11-15) × (1 + 123/(1024)) = 0.0700

Other floating point formats have similar formulas. For example, if you’ve got an IEEE 754 32-bit floating point number, you can break it apart into a 1-bit sign s, an 8-bit exponent e and a 23-bit mantissa f. The formula for 32-bit floats is this:

(-1)^s × 2^(e-127) × (1 + f/(2^23))

It is possible to do math with floating-point numbers, just using integer arithmetic involving those whole numbers s, e and f. That’s what computer hardware does. If you think about it long enough, you can figure out how. As an exercise, I suggest trying to figure out how to multiply two floating-point numbers broken out into their e and f parts, using integer math only - no fractions, no floats! Hint: one part of the job involves adding the first e to the second e and subtracting something…

Note: we talked about how zero is a special case, but IEEE floating point has other special cases such as “Not-a-Number”, known as NaN. I’m skipping over that special stuff.

Fun fact: Two different floating-point bit patterns are never equal (they always represent different numbers)… except that “positive zero” equals “negative zero”.

Fun fact: if two floating point numbers are both positive, you can compare the bit patterns directly to find out which number is bigger. For example, 5.125 is bigger than 0.07, so the corresponding bit pattern 0100010100100000 is bigger than the bit pattern for 0.07, 0010110001111011. This also means you can increment a bit pattern by one to find out what the next larger floating-point number is (just be careful not to pass infinity). The numeric difference between two adjacent floating-point numbers, such as 0000111001001110 and 0000111001001111, is called an ULP.

Why posits?

The “posit” is a core component of third-generation universal numbers (type-III unums). They are described in this paper.

You can think of them as an outgrowth of the traditional floating-point number format - they may be evolved from older unum designs, but at first glance they resemble floating point more than they resemble their predecessors.

I’m going to talk about 16-bit posits because small bit patterns are easier to discuss, but posits can have almost any size - 64 bits, 8 bits, whatever.

Remember the 16-bit floating-point format we just talked about? The largest number it can handle is 65504. The next larger bit pattern is called “infinity”, even though 66000 doesn’t seem very close to infinity. A 16-bit posit, however, has a maximum value of about 268 million. That’s because, as you increase the bit pattern inside a posit number, the number it represents will get bigger faster than a floating-point number gets bigger.

Actually, if you take the biggest 16-bit unum, 268 million, and decrement the bit pattern, it shrinks by a factor of 2, to 134 million. Decrease it again and it shrinks to 67 million. The distance between adjacent numbers in this range is immense, and the precision is terrible! Despite this, posits may be better than ordinary floating point for four reasons:

- Close to the number 1, posits have better precision than floating point. This is useful because numbers close to 1 are very common. 16-bit floating point always gives you slightly more than 3 significant digits (11 bits), but posits give you almost one extra significant digit near the number 1.0 (13-14 bits). For example, if you try to store π (3.14159265) in a 16-bit float, the closest representation is 0 10000 1001001000, which means 3.1406, but the closest posit to π is 0 10 1 100100100010, which means 3.14160.

- Posits can represent large and tiny numbers that floats simply can’t. It’s easy to complain about “inaccuracy” when 74 million gets rounded off to 67 million, but 67 million is much closer to the correct result than “infinity”. It’s also useful that you can store very tiny numbers that would have simply been rounded off to zero in a traditional floating-point format.

- Posits tend to produce more accurate results for most common functions including addition/subtraction, multiplication, reciprocal, and square root.

- The posit standard - if that’s really a thing - makes more promises about accuracy and repeatability across platforms than standard floating point (says the paper, “an incorrect value in the last bit for e^x, say, should be treated the way we would treat a computer system that tells us 2 + 2 = 5”.) Oh, and it promises a fused dot product operator and subsets thereof, such as fused multiply-add - but the listed maximum accumulator size for this starts to get huge around 32 bits of precision, which makes me wonder about its performance, and wonder whether the perfect LINPACK result in the paper relies on this huge accumulator.

- Posits are part of the type-III unum design, which I expect to be really cool.

They do have a few disadvantages:

- Real-world hardware doesn’t support posits (so far).

- Posits don’t distinguish between positive infinity, negative infinity and NaN. This seems like a major strategic mistake to me that will hinder adoption of posits. If you want people to use posits in the real world, they need behavior that is very similar to floats so that when you add posit hardware to a GPU or CPU, it can be adopted quickly as a drop-in replacement for floats in many applications. This would allow the traditional float hardware to be deprecated at the same time, or soon afterward (reducing FP footprint and performance). At the very least, I would expect there to be three distinct bit patterns for positive infinity, negative infinity and quiet NaN (signaling NaN is rarely used, although I’ve heard of applications such as JavaScript interpreters that use many distinct NaN bit patterns.) It is less important to have two different zeros, because rounding to zero rarely happens in posit arithmetic, but the more similar they are to traditional floats, the easier they are to adopt.

- The paper hints that, in some ways, posits are easier to implement in hardware than traditional floating point. But then I see the claim that since there is no NaN, “the calculation is interrupted, and the interrupt handler can be set to report the error and its cause… this simplifies the hardware considerably.” How so? Exception handling hardware is not cheap or easy (though at least it tends to already exist in most hardware). Nor is it cheap to fix zillions of lines of existing code that was written with quiet NaNs in mind. Does Gustafson (the inventor) hope that hardware makers will be happy to support two separate sets of hardware in perpetuity for posits and traditional floating point?

How posits work

A posit has four parts, and three of them you already know about:

- Sign bit

- Regime

- Exponent (but in a posit, it’s not simply the first-1 location)

- Mantissa (fraction bits)

The new “regime” part acts like a “super exponent” - it makes the number bigger or smaller much faster than the exponent does. It is special because has a variable size; it uses few bits if the number is close to 1, or many bits if the number is extremely large, or extremely close to zero.

The regime part holds a number in a special run-length encoding, and the number of bits in the regime is almost unlimited, because it’s allowed to use up every bit other than the sign bit. In a 16-bit posit there are only 29 possible bit patterns for the regime. Here is a complete list of them:

| Bit pattern | Number of bits | Regime value r |

| 000000000000001 | 15 | -14 |

| 00000000000001 | 14 | -13 |

| 0000000000001 | 13 | -12 |

| 000000000001 | 12 | -11 |

| 00000000001 | 11 | -10 |

| 0000000001 | 10 | -9 |

| 000000001 | 9 | -8 |

| 00000001 | 8 | -7 |

| 0000001 | 7 | -6 |

| 000001 | 6 | -5 |

| 00001 | 5 | -4 |

| 0001 | 4 | -3 |

| 001 | 3 | -2 |

| 01 | 2 | -1 |

| 10 | 2 | 0 |

| 110 | 3 | 1 |

| 1110 | 4 | 2 |

| 11110 | 5 | 3 |

| 111110 | 6 | 4 |

| 1111110 | 7 | 5 |

| 11111110 | 8 | 6 |

| 111111110 | 9 | 7 |

| 1111111110 | 10 | 8 |

| 11111111110 | 11 | 9 |

| 111111111110 | 12 | 11 |

| 1111111111110 | 13 | 12 |

| 11111111111110 | 14 | 13 |

| 111111111111110 | 15 | 14 |

If m is the number of identical bits, then r = m-1 when the first bit is 1, or -m when the first bit is 0.

The exponent field e has a fixed size, unless it is too small to fit (for example, if r=14, the exponent field must have a size of zero), and whatever is left over is the fraction bits f.

Perhaps the easiest way to explain the “regime” is with a formula. Just like floats, posits have a “location where the first 1 appears”, but it works a little differently in posits for two reasons. The first reason is that there is no “bias” parameter. In 16-bit floats you saw that the location to the left of the point was labeled 15, and this number 15 is called the “bias”. Posits don’t use a bias, so we will call the location to the left of the point “zero” instead. Therefore, the first “1” location for π (3.1415… = 11.00100100010…) is 1, and the first-1 location of binary 0.01 (0.25) is -2.

Posits use this formula for the first-1 location:

First1Location = r × (2^NumberOfExponentBits) + e

For example, if two bits are reserved for the exponent e, and e=1, and r=3 then

First1Location = 3 × (2^2) + 1 = 13

However, a standard 16-bit posit reserves only one single bit for e, so the formula becomes

First1Location = r × 2 + e

If “zero” is the location to the left of the point, a 16-bit floating point number must have a first-1 location between -15 and 16. In contrast, a 16-bit posit has a wider range, from -28 to 28. Let’s look at a couple of examples:

- If we want to store π, the First1Location=1, so r=0 and e=1. In this case the bit pattern for the regime is 10, which leaves enough space for 12 fraction bits, and the complete bit pattern is 0 10 1 100100100010.

- When the point location is 28, r=14 and the regime consumes all available bits, so e=0 and f=0 and the value of the number is

1<<28 = 268435456, approximately 268 million (X<<Ymeans “multiply X by two to the power of Y” in computer programming). Since there are no fraction bits, we know that this number is extremely imprecise.

There is a special rule for negative numbers: you must do two’s complement negation on it (flip all the bits and add one). I guess the reason for this rule is that it makes some hardware or software circuitry simpler in some way? In any case, let’s go through two examples of negative numbers.

- If we want to store the number -1, that’s still -1 in binary and First1Location=0, so r=0 and e=0. The bit pattern for the regime is 10, which leaves enough space for 12 fraction bits. The bit pattern for +1 would be 0 10 0 000000000000, but for a negative number we negate it (flip all bits, then add one to the bit pattern), so we get 1 10 0 000000000000.

- If we want to store the number -1234, that’s binary -10011010010 and First1Location=10, so r=5 and e=0. The bit pattern for r=5 is 1111110, which leaves us with 7 fraction bits, so the fraction must be rounded off from 0011010010 to 0011010. So the bit pattern for +1234 would be 0 1111110 0 0011010, which has been rounded to 1232. For the negative number we negate the flip the bits and add one, which gives us 1 0000001 1 1100110.

Finally, posits have two special values:

- If all bits are 0, it represents zero.

- If all bits are 0 except the sign bit, it represents positive or negative infinity.

Fun fact: 32-bit posits above 4.3 billion have less precision than floats, but 32-bit posits below 16.7 million (and above its reciprocal) have more precision than floats.

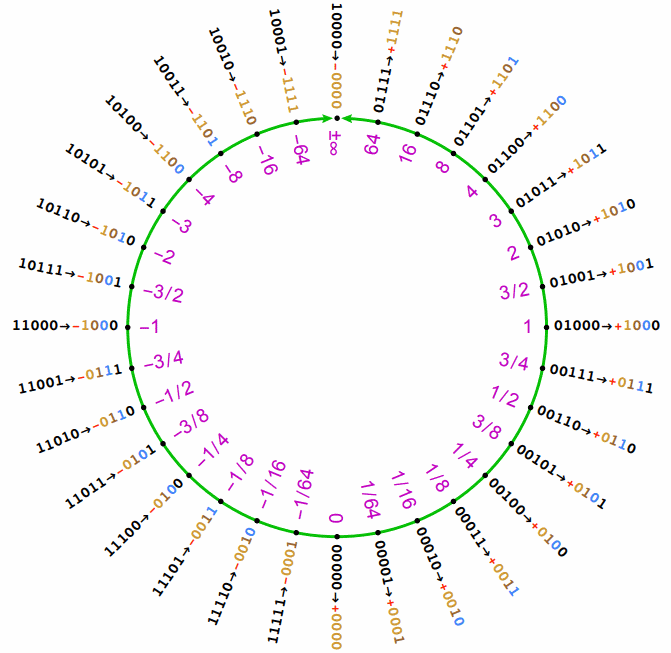

Five-bit posits

A five-bit posit is large enough to have all four parts (sign, regime, exponent and fraction) but small enough to draw every value in one diagram:

(Image from “Posit Arithmetic”, John Gustafson)

Pick a bit pattern and see if you can understand how the regime (yellow) combines with the exponent (blue) and the fraction (black) to represent a number. Take 11011, for example. It’s negative, so we have to flip the bits and add one before extracting the regime, exponent, and fraction (-11011 = 00101 => r=-1, e=0, f=1). First1Location = r×2+e = -2, so we have binary 0.011 = 3/8 = 0.375.

Is this the best representation?

I have little doubt that posits work significantly better than floats. An independent study on by Lindstrom et al about “Alternatives to IEEE Floating Point”, confirms that posits give more accurate results than floats in practice. However, it also finds that posits aren’t “universally” best and don’t necessarily give higher accuracy than, for example, Elias’s δ code from 1975. It seems fair to say, though, that posits are one of the “best in class” formats, and it is plausible that they are easier to implement in hardware than the Elias δ/ω formats.

Posits aren’t the full story, though - they provide a foundation for type-III unums, but they are not unums: like floating point, they don’t quantify the amount of error that has occurred during calculations, and they can’t give you bounds on what the “true” answer is.

In 64-bit floating point, 0.1 + 0.2 ≠ 0.3, even though 0.1 + 0.2 = 0.3 in 32-bit floating point. Posits don’t eliminate this kind of phenomenon; decimal numbers cannot be represented exactly in posits either, and due to rounding errors you can’t expect X/10 + Y/10 to produce exactly the same bit pattern as (X+Y)/10 in all cases.

In contrast, in unum arithmetic, when you can ask the computer “is 0.1 + 0.2 = 0.3?” it can give you a more correct answer: maybe. Unums don’t store 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3 exactly, but unum arithmetic can detect that there is overlap between 0.3 and whatever 0.1+0.2 is equal to, so that they may be equal, and the system can quantify the equalness by telling you the maximum amount that 0.1+0.2 might differ from 0.3 (something like “they are within 0.000004% of each other”). By the way, you can rely on small integers like 5 or 17 to be stored exactly, so unum arithmetic can report with certainty that 5+17 = 22.

So what is a type-III unum?

Right now, Google won’t tell me. I clicked on each of the top ten results for this query and not a single one discussed them in any detail. However, there’s a site called posithub.org whose “news” page pointed me to… “sonums” that are “better than #posits”, huh? The site also advertised a video called “Strength in Numbers: Unums and the quest for reliable arithmetic” which… barely talked about unums at all, and only type-I unums.

Finally I find buried in section 3.6 of a document about posits, a “Sneak Preview” of “Valid Arithmetic”.

“Valid” doesn’t mean what it normally means. It’s a confusing term that Google won’t understand, meaning “a range of posits with ubits”. I glean that type-3 unums work something like this:

1. There is a modified posit with a ubit

The ubit, invented for the original type-I unums, indicates imprecision. The integer 123 is exactly 123, so the ubit is 0, whereas 0.3 or π are inexact and the ubit is 1.

The ubit becomes the least-significant bit. For example, the normal 16-bit posit for π is 0 10 1 100100100010; the modified posit would be 0 10 1 10010010000 1 - and notice that the last two bits have changed.

Think of this bit pattern as an ordinary 16-bit integer for a moment (it’s 22817), and let’s write down the closest bit patterns to it (22816 and 22818):

(22816) 0 10 1 10010010000 0 = 3.140625 (exact)

(22817) 0 10 1 10010010000 1

(22818) 0 10 1 10010010001 0 = 3.1416015625 (exact)

This is a hint about what the bit pattern means. It means “somewhere between 3.140625 and 3.1416015625” (but not exactly equal to either of them).

2. Two modified posits form an interval

TODO…

Concern

Earlier I complained that posits aren’t really a “drop-in” replacement for floats in many applications, due to significant differences in behavior between the two.

- Posits don’t distinguish between positive infinity, negative infinity and NaN. Some applications expect that division by zero will give positive infinity, which will then compare as “greater” than all other numbers, which won’t work with posits. Meanwhile, hardware treats NaN as “not equal to itself” so some applications detect an error by comparing a value to itself.

- 64-bit posits can’t represent the maximum corresponding float (DBL_MAX)

- The smallest posit works slightly differently than the smallest floating-point number (double.Epsilon in C#). A few applications may use this number incorrectly, treating it like an ULP instead. Most coders will quickly realize this is wrong, because x+epsilon = x in most cases. If x is tiny enough, though, x+epsilon ≠ x in float arithmetic, unlike posit arithmetic where x+PositEpsilon = x is always true unless

x == 0. (I haven’t found anything useful that you can do with this number; a simple remedy is to leave it at the same numeric value used for floats, just so that epsilon+epsilon ≠ epsilon as one would expect.) - There is only one zero, not two. This matters in apps that expect x/+0 to be positive infinity and x/-0 to be negative infinity. This expectation may appear indirectly: an app may expect that a number that is divided by some number above 1 enough times will reach zero, and then division by it will yield an infinity of the correct sign.

- Posits have a smaller “safe increment range” than floats: if you increment a float repeatedly with a loop like

float f = 0; for (f = 0; ++f != f;) {},fwill be larger for float than posit. A few applications may define this upper limit as a constant, and potentially malfunction if posits are used instead.

I believe that if posits are to someday replace floats, there needs to be a way to achieve a higher level of compatibility.