Top 11 principles & practices of programming

Fourth draft 08 Apr 2020“For the year 2020, we determined the total Cost of Poor Software Quality (CPSQ) in the US is $2.08 trillion (T).” - CISQ report published after this blog post

So you’ve got the training: you learned how to use XML, HTML, SQL, Java, Python, hashtables, mutexes, binary search trees, maybe you even took a course in 3D graphics or compiler design. You were told to use constants and unit tests and not to use global variables or goto. What’s missing from this list? Only some of the most powerful pinciples and practices of programming!

This post will teach you to…

- See through the eye of the Tool Writer

- Properly prioritize principles

- Separate concerns

- Avoid repeating patterns

- Use the correct amount of abstractions

- Promote reusability and organize your code well

- Write good tests

- Pick good names

- Use comments appropriately

- Learn about functional programming

- Know what things cost

- Keep improving!

0. Seeing Through The Eye of the Tool Writer

Since watching Bret Victor’s “Inventing on Principle” I was sure I wanted to “Invent on Principle” as he suggested, but the tricky part is figuring out what my Big Principle is. One principle I’ve homed in on is that easy-sounding things should be easy.

Programming is full of things that seem like they should be easy, but are unnecessarily hard in practice. Things like drawing graphics efficiently (you can start easily with Windows Forms but if you want efficient drawing you have to make this massive leap over to DirectX, in which case, good luck implementing your GUI widgets by hand) playing music and sounds (okay, playing a .wav file might be a simple static method call, but generating audio continuously or playing an mp3 or opus stream might be far more difficult), or keeping a user interface synchronized with the underlying data model (but see SwiftUI, Assisticant, MobX/KnockoutJS for reactive solutions in Swift, C# and JS respectively). And no matter how good a product’s user interface might be, it often happens that its internal components are confusing and laborious to use, with a design that is messy, inflexible, unportable, and expensive to maintain.

The basic idea of making software easy is pretty simple:

- Imagine what your code would look like if your task were as easy as possible. And maybe this is ordinary code, or maybe it’s a flow diagram, or maybe it’s a specification that a machine generates code from.

- Next, you build the tool that makes your dream a reality - it could be as small as a single function, or as large as a new programming language or debugger infrastructure.

And so I long to be a tools developer, to make tools that will make easy-sounding things actually straightforward.

But this basic separation, of making a tool to make something easier, and then using that tool, is not specific to tools developers. Instead, this is something all developers should use in their everyday work.

Here’s a small code snippet I saw recently (names have been changed to protect the guilty):

var nameStem = metaData.tableName;

if (metaData.tableName.EndsWith("_VERSIONS"))

{

nameStem = metaData.tableName.Substring(0,

obj.tableName.Length - ("_VERSIONS").Length);

}

if (metaData.tableName.EndsWith("_RECORD"))

{

nameStem = metaData.tableName.Substring(0,

obj.tableName.Length - ("_RECORD").Length);

}

I could criticize this is as a a violation of the well-known Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) principle, because the same code pattern appears twice. But perhaps a simpler, more general way to look at it is as a failure of the developer to make things easy, and specifically, as a failure to use that general technique of separating the code into a general tool, on the one hand, and code to do a specific task, on the other.

So I imagined what the code would look like if it had been easier to write:

var baseName = metaData.tableName.WithoutSuffix("_VERSIONS")

.WithoutSuffix("_RECORD");

This doesn’t do precisely the same thing as the original code, but I happen to know that each tableName only has a single suffix, so in practice it is the same. Notice that this code isn’t just easier to write. It is at least as important that this is easier to read (after all I was reading this code as part of my job.)

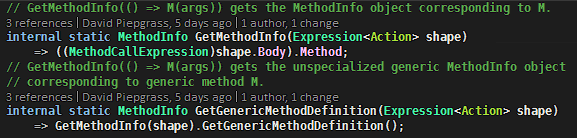

And then you write the tool:

public static string WithoutSuffix(this string s, string suffix) =>

s.EndsWith(suffix) ? s.Substring(0, s.Length - suffix.Length) : s;

Remarkably, within days of creating this new tool, I had used it multiple times in my own code, and I was rather amazed that I had never before thought to write this function. I had internalized the DRY principle well enough to notice the repetition and remove it, but as a tools developer at heart, it was ironic not to have noticed earlier this opportunity to build a tool.

If you take one thing away from this post, let it be this basic separation: imagine things are easy, then make them that way.

Often the best way to solve a large problem involves creating a large tool that is fairly elaborate. Often this will not be acceptable to management.

But as the example above illustrates, often there are little tools you can make, that will improve your ability to write software without the cost of making a large tool. The little tool might not be as broadly applicable as a bigger, more ideal tool that you can imagine, and it might not even reduce total development time as much as a bigger tool, but the little one will be easier to get through management, the time needed to build it will be more predictable, and by making a small tool, you might learn things that will help you build a larger and better tool later.

So if there’s one technique you learn here today, let this be it.

But there are others. I have seen many proposals for programming principles: SOLID, KISS, YAGNI, composition, Law of Demeter, avoid premature optimization, avoid high computational complexity, test-driven development, object orientation, avoid mutability, blah blah blah. But which principles are the most important? Often, principles come into conflict with each other; it is hard, and sometimes impossible, to satisfy every good-sounding principle at the same time.

So as a senior developer, allow me to summarize what I think the most important principles are, in approximate order of priority.

1. Separate concerns!!

A program is like a house: just as walls give a house structure, separation of concerns gives a program structure. Most programming languages do not facilitate separation of concerns because they allow almost anything to touch almost anything else. Programmer discipline is required to create imaginary walls where no connections are allowed. For example, a language typically can’t stop a business-rules class from directly running SQL update commands, so the wall between the two rests only in the minds of the developers.

I think some people “solve” this lack of compiler enforcement with “microservices architectures”, but any solution that involves huge amounts of otherwise unnecessary plumbing code is a poor solution. Good discipline lets you do the same thing with less code.

Concerns should be separated both “vertically” and “horizontally”. Vertical separation is a stack of dependencies: module C depends on module B which depends on module A. Horizontal separation is unrelatedness: copying text to the clipboard is separate from deleting text, which is separate from the Undo Stack. The Cut command may use all three of these things, but it should be separate from them vertically, and they are separate from each other horizontally.

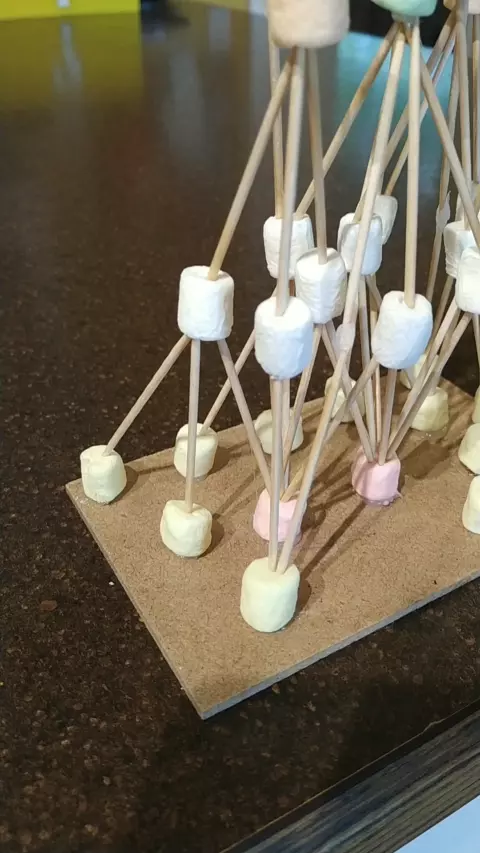

You can visualize separation of concerns as a 3-D pyramid of modules, with high-level functionality at the top, and low level functionality at the bottom.

Diagram is not to scale: I should have chopped the toothpicks in half first.

As the diagram illustrates, it should be possible to arrange all modules in a vertical way so that there are no horizontal or upward connections between them: higher levels only use lower levels.

- Some modules will be very popular and used by many others (bottom pink marshmallows).

- some will use many modules (but not an excessive number, with the exception of wiring for dependency injection)

- Some will use or be used by only one module

- There can be multiple programs or entry points based on the same modules (upper pink marshmallows).

- Most software will have more vertical levels than the five shown here, but modules can reach down multiple levels to reach their dependencies (green marshmallows).

2. The Generalized Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) principle

Avoid not just repeating information or business logic in multiple places, but minimize repetition of any patterns whatsoever. The larger or more frequent a pattern is, the more important it is to avoid repeating it.

Elegant code minimizes the number of tokens in the program (not including comments, and within reason).

Sometimes, repetition is obvious, sometimes not. To me, these two classes are highly repetitive:

public class EmailAddress

{

public string UserName { get; }

public string DomainName { get; }

public EmailAddress(string userName, string domainName) {

UserName = userName;

DomainName = domainName;

ThrowIfInvalidAddress();

}

public override string ToString() => $"{UserName}@{Domain}";

...

}

public struct Address

{

public string UnitNumber { get; set; }

public string ShortAddress { get; set; }

public Municipality Municipality { get; set; }

public string PostalCode { get; set; }

public Address(string unitNumber, string shortAddress, Municipality municipality, string postalCode) {

unitNumber = UnitNumber;

shortAddress = ShortAddress;

municipality = Municipality;

postalCode = PostalCode;

ThrowIfInvalidAddress();

}

...

}

In C# or Java there is no way to write this code in a shorter way, but I hated code like this so much that I built LeMP.

I used to think DRY was my #1 most important principle, because the idea of organizing code well, including Separation Of Concerns, was so deeply ingrained in my psyche that it had become invisible to me. Encountering a codebase that was disorganized and mixed concerns all over the place reminded me that Generalized DRY does not reign supreme… but it’s still really important.

Don’t. Repeat. Stuff. And if you do repeat stuff, at least slap a // TODO: This violates DRY, refactor it! on that sucker.

3. Use the correct amount of abstraction: no more, no less

Create functions and abstractions appropriately, but avoid excessive layering/wrapping.

Wrapping is often motivated by prior failure to refactor, or failure to test, leading to brittle code you don’t dare touch. But having lots of layers, that basically have the same responsibility, with confusingly similar names… well, it’s confusing. You’re taking a bad situation and making it worse. Don’t do that (unless required).

Too many abstractions can also occur because you are imagining several use cases that may never materialize, so you write a “framework” for these imaginary use cases. This is where YAGNI comes in: You Ain’t Gonna Need It.

Don’t design large frameworks. Design libraries that are small, yet flexible and powerful within that constraint of smallness. But do design them. You do need some layers: real-world functionality should usually be built upon tools that are built on other tools.

Focus mostly on features that you will actually use; considering those imaginary use cases is fine, but it should influence the code in ways other than making it larger. For example, imagine ways you might improve the implementation of a component later, and then make sure that the public interface is not incompaible with that hypothetical implementation. All too often I see interfaces that were designed for only one very specific (and poorly-thought-out) implementation. That’s not what interfaces are for, guys.

4. Promote reusability by organizing your code into separate general and specific parts

This is another perspective on #0 and #1, Path of the Tool Writer and Separation of Concerns. Another way to say it is “separate things that change from things that stay the same”; tools change less than the things you build on top of the tools.

Suppose you’re adding support for profile pictures of your users, and you want to cache these pictures in memory. Don’t just write a PictureCache class to cache pictures! Definitely don’t write a ProfilePictureCache that is specifically for profile pictures. Instead, start by writing an ObjectCache for caching anything, so that you can use it to cache other things later. Also, check the Standard Library (and popular packages) for your language to see if there’s already a cache that would meet your needs. If the picture cache has special requirements that somehow only apply to pictures, try to put as much code as possible in ObjectCache and then write small a PictureCache wrapper that uses ObjectCache but also supports the special requirements.

The strategy pattern is super useful for promoting reusability. The idea is to write something general and then offer places to “plug in” specific knowledge and functionality. Strategies are usually functions or interfaces. In an Object Cache, for example, a strategy might be a function that figures out the size of each object (assuming your programming language offers no built-in way to do this). This function should typically be a constructor parameter of the Object Cache, but it may be a property so that the strategy can be changed after the cache is created. Traditionally, object-oriented inheritance was used for this kind of thing, but the strategy pattern is often better because (1) a single class or component can support multiple kinds of strategy at the same time, and (2) strategies can sometimes be changed after the class is constructed.

To put this a third way, design your interfaces, classes, modules and libraries to be generic, ignorant, and reusable. If your code isn’t separated properly, it will be designed for a specific business use inside the specific app you’ve been hired to work on. It may seem appealing that you’re “working on the problem domain” and “tailoring your code to your employer’s needs”, but chances are that you’re also making a mess that is hard to understand, isn’t flexible enough to adapt to new requirements, and can’t be taken out of the current app and be plugged into a new app that has a better architecture.

This division between general and specific should extend right up to the way you divide your software into folders, namespaces/packages, and DLLs/libraries/projects. If your software doesn’t have a “general-purpose” or “common” folder, add one. I suggest three levels of specificness:

- Totally general stuff that would be useful in many different industries, e.g. graphics primitives, RPC protocols, caches, advanced data structures, an undo stack.

- Stuff that is specific but not limited to your app, e.g. code dealing with a file or database for DLS land parcel lookup, code to compute retail taxes for goods in specific states

- High-level features in a product your company sells. If possible, parts of these features should be pushed down into layers 1 and 2.

Finally, since high-level things depend on lower-level things (but not vice versa), designing low-level parts well (especially the interfaces which which they are used) is more important than designing high-level parts well.

5. Avoid multiplying the number of code entities beyond reason

When someone is reading your code, every new and separate entity is something that the reader has to expend mental energy to keep track of. Try to reduce this mental energy requirement, and your code may end up shorter as a happy side effect. For example, I realized that “logging” and “reporting a set of warnings and errors to a user” are mostly the same thing, so in the Loyc.Essentials way of doing things you would use the same classes and the same interface IMessageSink for both (sometimes I wonder if no one else has noticed this).

Similarly I often see interfaces like ISomethingRetriever whose job is to retrieve some kind of object given some kind of key. That’s basically a dictionary! Just implement IReadOnlyDictionary, you fool, or whatever your language’s equivalent is. If you really do need a new interface, figure out if you can at least make it similar to something else in your language’s standard library, if possible. Do not create a new and different interface every time you need to retrieve a new kind of object. Your app probably does not need to define a hundred separate interfaces.

This is similar to #2 (DRY), but different. For one thing, sometimes things that are fundamentally similar do not appear similar at first, and you might not notice the repetition. So here I am saying you should look deeply for patterns, and when you find them, unify them.

For another thing, the merged entity does not always have to be smaller than the parts it was formed from, nor do you necessarily have to physically merge the parts together. Instead, the goal is to make sure the code is understandable by not overloading people. A simple example is taking take three small classes and turning them into private inner classes of a fourth class. This maintains a separation of concerns between the three classes, but someone reading the code probably only needs to keep track of the single outer class in their head.

Another example comes from GPS software I wrote called FastNav, a mapping system that provides turn-by-turn directions to drivers. I designed it to be very flexible, and so there were several separate classes for things like

- Keeping track of which road a vehicle is on, or closest to

- Managing route calculations, and recalculations when a vehicle goes off the calculated route

- Displaying an arrow representing the vehicle on the map control

- Displaying a line representing a route on the map control

- Speaking instructions for the next turn out loud

The software might not be used in a vehicle; it could be used in a desktop application that shows many vehicles or no vehicles, for example, and routes weren’t necessarily related to vehicles per se. Therefore, I left it up to the user to create all these classes and connect them to each other according to their individual needs. However, my boss found the large set of classes bewildering. He wanted something easier to use. So I got the idea to create a “front” class called VehicleState that represents a vehicle and its route, tieing together all of these classes into a single class.

I didn’t actually merge the existing classes together, which would violate the #1 principle, Separation of Concerns. Instead I simply made them internal and did not expose them publicly in the SDK. Users would create one or more VehicleState objects and then deactivate any functionality they didn’t need. Potentially this meant some memory would sometimes be wasted on unused objects, but it was worthwhile because it made the SDK much easier to use.

6. Write good tests (or prove correctness)

If you’ve got tools that can mathematically prove important properties of your software, wow, good for you. For everyone else there’s automated tests.

Automated tests have major benefits:

- It’s a lot faster than manual testing

- You can do a lot of test variations (using for-loops and other mechanisms) for better confidence that your code works

- Tests influence how code is structured. Badly structured code tends to be hard to test! By writing tests (especially without mocks) you’ll be forced to write code that is good enough to test. Arguably, practices like test-driven development (TDD) improve code quality by influencing code structure, especially among less-experienced developers who aren’t sure yet what good code looks like. Tests should have access to “internal” members of types, though (in C#, use the InternalsVisibleTo attribute if your tests are in a different DLL).

- Making your app safe for changes. You want to be able to change things and see if you broke something major without any manual testing. Facebook’s motto is “Move fast and break things”, but it’s not literally OK for developers to break Facebook. If there are comprehensive tests, developers can be trusted to change things more, which means crufty old code can be improved. Use code-coverage tools to check (approximately) how much you’ve tested.

You don’t need “unit” tests for everything, in the sense of testing divorced from dependencies. I don’t know where this idea came from that the dependencies of the component under test have to be fake (test doubles). It’s okay if you are testing component C and C uses components A and B. It’s especially okay if you also have separate tests for A and B by themselves.

Avoid using mocks. In my experience, well-designed software never needs mocks in its tests. If you can’t fully test the software without mocks, it means the software is structured incorrectly. “White-box” testing may require mocks to check implementation details, but this reduces your freedom to change the internal design of the component. With this form of testing, when you change the internal design you may cause mock-based tests to fail, even if the new implementation is correct and working properly. This is not good.

You have a limited amount of time to write tests, so your first priority should be to make sure that basic functionality - the things you expect users or customers to do with your software - work. Your other main priorities should be making sure that less common, more obscure functionality works; that edge cases work; and that corner cases work. Your lowest priority should be making sure a constructor throws an exception when “null” is passed to it.

In addition to basic tests, use complex tests with randomized and/or realistic data, in order to test your objects in their most complicated states.

Good tests are written with the same discipline as the rest of the code. Don’t repeat yourself, separate concerns, this all stays relevant.

In particular, minimize the size of each test - not the test methods, but the tests themselves. Some people propose rules like “each test function should only test one thing!” Wrong. Your primary goal in testing is to test as thoroughly as possible in the time you have available. One thing that will help you do this is to make each test as compact as possible, so that you can write more tests in the same amount of time, and so that you can keep track of your tests more easily (500 lines of tests is going to be easier to keep track of than 1500).

For example, in much of my Enhanced C# test suite, there are two tests per one line of code. Pretty compact, right? Here’s an example:

[Test]

public void CsSimpleVarDecls()

{

Stmt("Foo a;", F.Vars(Foo, a));

Stmt("Foo.x a;", F.Vars(F.Dot(Foo, x), a));

Stmt("int a;", F.Vars(F.Int32, a));

Stmt("int[] a;", F.Vars(F.Of(S.Array, S.Int32), a));

Stmt("Foo[] a;", F.Vars(F.Of(S.Array, Foo), a));

Stmt("Foo a, b = c;", F.Vars(Foo, a, F.Call(S.Assign, b, c)));

// The parser doesn't worry about treating this as a keyword

Stmt("dynamic a;", F.Vars(_("dynamic"), a));

Stmt("@dynamic a;", F.Vars(_("dynamic").SetBaseStyle(NodeStyle.VerbatimId), a));

Stmt("var a;", F.Vars(_(S.Missing), a));

Stmt("@var a;", F.Vars(_("var").SetBaseStyle(NodeStyle.VerbatimId), a));

}

Each line of code ensures that the string on the left corresponds to the syntax tree on the right. I’ve used some techniques to make the syntax trees compact: F is a very short name for the syntax-tree factory; a, b, c and Foo are variables that represent the identifiers “a”, “b”, “c” and “Foo”; and the _("var") function is a questionable abbreviation for F.Id("var") which itself is an abbreviation for ‘create an object to represent an identifier named “var”’ (I called it _ so that my eyes could easily ignore it - I wanted to emphasize the identifier’s name and de-emphasize the fact that a factory was being used to create an identifier object.)

But the test method is located in a base class where the Stmt (statement test) method is abstract. There are two derived classes: one makes sure that the string on the left is parsed into the syntax tree on the right, while the other makes sure that when the syntax tree is printed into a string, it’s the string on the left. Thus, each line of code is actually two tests. Of course, there are some tests that only apply to one or the other (e.g. there are tests to check what the parser does in case of syntax errors, and other tests to see what happens when the printer is given a syntax tree that the parser would never produce).

Imagine how inefficent it would be if I didn’t use these techniques and needed to write six lines of code for every test:

// Parsing tests!

[Test]

public void CsTestVariableDeclaration_Foo_a()

{

var syntaxTree = F.Vars(F.Id("Foo"), F.Id("a"));

Stmt("Foo a;", syntaxTree);

}

[Test]

public void CsTestVariableDeclaration_Foo_x_a()

{

var syntaxTree = F.Vars(F.Dot(F.Id("Foo"), F.Id("x")), F.Id("a"));

Stmt("Foo.x a;", syntaxTree);

}

// TODO: repeat the same tests for converting back to string

Such a clunky way of writing tests would cause me to write fewer tests, so I’d end up with more bugs, and at the same time the code would be longer, so it would be harder to read the code and get a sense of what I have already tested and what I may have missed.

I do similar things for interfaces. Often if you implement an interface multiple times, there are certain rules that every implementation has to follow. You can get a lot of mileage by writing a single test fixture to ensure that every implementation follows these rules.

7. Pick good names

You probably know the standard rules:

- Most methods should be named with a verb phrase, e.g. AddItem, FindMatchingItem, CreateRecord. Try to begin boolean methods with

isorhas. - Very long names are fine, except on frequently-used stuff.

- If a value always has a certain unit, include the unit in the name e.g.

sizeInKB,widthPixels(necessary only in languages without unit checking, i.e. most languages)

A lot could be said about naming, but in brief I suggest spending time thinking about names. Also, write documentation that describes things in a different way than the names do, because people often read documentation when they aren’t sure what the name means. Be on the lookout for ambiguity and vagueness. It may seem clear to you that a RecordDependencyPropertyCollection is a sequence (whose order is not important) of pieces of metadata about dependencies between pairs of records in your application, but I can assure you this is not obvious from the name. Sometimes a better name will be more clear; other times, nothing short of comments/documentation will clarify the purpose of something.

When debugging is done and the code is ready to commit, that’s a good time to reconsider the names you chose before. Or, wait three months and see if the meaning of your names is still clear after you’ve been working on something completely different. The passage of time causes your brain to forget things that seemed obvious at the time, which allows you to read your own code with fresh eyes. Take advantage of this opportunity to notice when your code is more confusing than you thought–and fix it.

8. Use comments appropriately

I often write documentation for a class before its code, which leads to clear thinking and good separation of concerns. (However, I must remember to review the documentation during the commit process, because I usually tweak my planned implementation midstream, potentially making the comment wrong from the very beginning!)

Documentation of high-level and large-scale entities (classes, modules) is often more important than documentation of small-scale entities (small functions and code blocks), because high-level comments can be extremely helpful to anyone who is new to the codebase (or to this area of the codebase). As you write these comments, make sure they are meaningful by keeping in mind who your audience is: someone who knows almost nothing about the code. Documentation of mutable state variables (e.g. invariants) is also a cheap way to help readers understand code more quickly.

A lot of code is self-documenting and doesn’t really need comments, although a short comment to summarize a code block can let someone avoid the painstaking work of actually reading the code. This is especially helpful when the reader has no clue what the code is for (e.g. because it encodes non-obvious business rules, or performs non-obvious preparatory steps for work done elsewhere). The reason to avoid comments is that when people update code, they often forget to change the comments to match the new code. But at least experienced readers already know that any given comment may be out-of-date.

However, code can only explain what code does. Comments are needed to explain why: what purpose the code serves, or why it is being done in a weird way, or why it is seemingly being done in the wrong module, or why it is doing something that seems redundant or unnecessary, or why X must happen before Y. Use comments to explain why, and to teach other developers when and how to use a component or function (if you don’t have dedicated documents for that).

In Visual Studio, CodeLens visually separates comments from code, encouraging developers to overlook comments when updating code. To reduce this effect, I shrink my CodeLens font vertically (Lucida Console size 7) but it only helps a little.

When writing documentation, keep in mind my #1 tip for technical writers: use examples. This post uses “for example” and “e.g.” over 15 times and I’m still not sure if it’s enough to get my ideas across.

9. Learn about functional programming, and use it

Understanding when and how to use functional programming ideas like immutability, persistent data structures, map/filter/reduce, lambdas, tuples, algebraic data types (or union types, or class hierarchies to simulate union types in C#) and higher-order functions is a crucial skill for intermediate and senior developers. I lament that introductory courses still teach nested for-loops before they teach map/filter, that “blocks” (procedures) in Scratch cannot return values, and that my university still teaches C++ to first-year students.

Traditional procedural and object-oriented programming has its uses, but if I could only choose one programming paradigm to use for everything, functional would be it.

10. Know what things cost

In 1974 Donald Knuth published a paper with the famous line “premature optimization is the root of all evil.” Few remember, however, that the title of this paper was “Structured Programming with go to Statements”, that the paper spoke at some length about optimization techniques, and that it was published at a time when computers were dramatically slower, profiling tools were poor, and overoptimization was a real problem in the software industry.

Throughout my career I’ve been mystified by programs that take more than a few seconds to start, since my own software never had a problem with startup time.

Except once. I was told that my WinForms-based app looked “too 1990s” and needed to be “upgraded” to WPF. Fast forward a few months, the shiny new WPF version was indeed more visually attractive, but when we shipped it, a customer complained that it took over 45 seconds to start on their ancient hardware (making this especially confusing to them, it had no splash screen.)

I was shocked. My software slow to start? Even on my own machine the startup time wasn’t great, at six seconds. Luckily when writing the WPF version, I used Update Controls (now known as Assisticant) and adhered strictly to the ideal MVVM separation of concerns between views and ViewModels. As a result, the old WinForms version still basically worked with the same ViewModels and back-end. I had left the WinForms code intact, waiting to be activated by a --winforms command-line option. The WinForms version started in about 5 seconds on the customer’s machine (and almost instantly on my own machine), so we suggested they use the WinForms version for the time being. Since virtually all my code was the same between the two versions, I knew that my own code performed well enough, but that WPF itself and the third-party WPF controls we bought somehow took over 40 seconds to initialize.

The company paid good money for those controls. Why were they so slow? I suspect people have learned the wrong lesson from “premature optimization is the root of all evil.” People act like it means “ignore performance completely until the problem is too bad to ignore any more.”

The WPF people certainly learned the wrong lesson. I did a test, creating a ListBox with 10,000 items in it, non-virtualized (for IsSelected bindings to work correctly), with no DataTemplate. Each item was just a string like "Item #1234". WinForms, of course, would never have a problem with such a small list, but in WPF the list consumed 80 megabytes of RAM and the ListBox took four seconds to handle a single press of the down arrow key, on a multi-core machine capable of running billions of instructions per second, per core.

Knuth said “We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil. Yet we should not pass up our opportunities in that critical 3%.” But premature optimization is not nearly as bad as not giving a f*ck, which is a far more common practice today. And surely Knuth exaggerates - 10% is a more likely number. When speed-critical code is written badly, 3% of the code might take 50% of CPU time, but once you optimize it, the same 3% is takes only 5% of the time, and now the slowest code is somewhere else and 10% of it is taking 50% of CPU time.

If you’re writing a library, like WPF or its 3rd-party controls, which parts of it are speed-critical? Well, the library could be used in thousands of different programs, but each program uses different parts of your library heavily. This implies that library authors should optimize much more than normal applications do, since a lot more of the code will be speed-critical for at least a few users. Likewise, the more users your app has, the more likely that one of your customers is stressing a code path that the others are not. Even if 3% of the code takes half the time, it’s not necessarily the same 3% for every customer!

As a library author who grew up at a time when my apps actually had to fit in 640K of RAM, rarely was my program small or fast enough at first, and I learned to care about performance like the folks of 1974. Without good profiling tools I’ve sometimes optimized the wrong things; still, let me share some lessons I’ve learned:

- If you haven’t already, learn about big-O performance metrics and use them to estimate how slow your software is. The short version of this is “nested loops are slow. And it doesn’t matter to the processor if the loop is in your code or if it is hidden from view in the standard library.” Also, hashtables are faster than sorted data structures which are much faster than linear scans through large lists.

- Big-O only matters if you can still decrease it. Once your big-O is as low as it can be (or almost as low as it can be), there are many other things to start worrying about.

- Keep in mind the dramatic difference in latency between access to L1/L2 cache, main memory, SSD, hard disks, and the internet.

- PC processors (desktop/laptop) have prediction-based optimizations so that executing predictable code paths is faster, and predictable memory access (especially sequentially) is faster. For example, virtual method calls are faster if the implementation is usually the same, “if” statements are very fast if the same path is usually taken, and arrays tend to be much faster than linked lists.

- Threads are costly to create and synchronization between processors is somewhat costly, so parallelizing tasks remains an art form for algorithms that are not embarrasingly parallel. When parallelizing, things to be aware of include Amdahl’s law, LMAX disruptor, and er… remind me to finish this list.

- Dynamic and interpreted languages (JavaScript, Python, old BASICs) tend to be 4 to 100 times slower than statically-typed, compiled languages, even if (like JavaScript) they are heavily optimized. Exceptions to this rule may include Julia (which has slow startup and high memory use in exchange for fast long-term performance), LuaJIT and PyPy. Plus, key parts of slow languages are written in fast languages (e.g. JavaScript’s new Map type will be fast because it is written in a fast language.)

- On some desktop processors, floating-point is almost as fast as integer math, but in some environments (e.g. IoT) floating point may be dramatically slower.

- Know about SIMD, though good opportunities to use it are rare.

- There are millions of pixels in modern screens, so drawing is slow in the same way scanning million-item arrays is slow, but worse because graphics memory is physically far from the CPU. GPUs speed things up using extreme concurrency, but they require specialized technology to program. General-purpose GPUs are widespread and useful for massively tasks such as simulation and machine learning.

- Working on massive datasets with big arrays in C++? Try Halide (they call it a “language”; it’s just a large C++ library.)

- Force your PC to run slower sometimes, to simulate users with older/cheaper hardware.

When you are contemplating whether to “heavily” optimize a program, you should use a profiler to find the slow parts before you do a lot of work. However, knowing what things cost will help you make decisions as a matter of course.

If you know what things cost, you might design a public-facing interface or multi-tier architecture correctly the first time, instead of having to do arduous workarounds and redesigns when it becomes clear that you made a big mistake. If you know what things cost, you hardly need any time at all to choose between List<> (array), Dictionary<,> (hashtable), SortedDictionary<,> (red-black tree), SortedList<,> (insertion-sorted array) or LINQ OrderBy (quicksort). Such decisions often have no impact on performance, but sometimes have a big impact. Better to avoid a slug (slowness bug) on day one, if you ask me.

11. Keep improving

Be on the lookout for new and better general-purpose techniques, and then actually use those techniques. For example, I am slightly irritated whenever I see professional developers using strings when they should be using Symbols. Why? Do you use strings in C# because it doesn’t have Symbols? But you’ve seen Symbols in Ruby and JavaScript (ES6) - take the lesson you learned in the other language and apply it to C# (Loyc.Interfaces on NuGet for C# includes a Symbol type.)

Other things I think are broadly useful include

- reactive libraries & frameworks (Assisticant for C#, MobX/Vue/KnockoutJS/Svelte for JavaScript),

- “semipersistent” data structures (

sorted-btreefor TypeScript/JS, ALists and hash trees for C# in Loyc.Collections), - Object-relational mappers (I’m not sure of the best options in this space),

- Macro-based languages for code generation (Rust, Clojure, Sweet.js for JavaScript, LeMP for C#, and please contact me personally for help with the latter)

- LES2, which is JSON-compatible, for storing data that contains code-like entities such as expressions

- Localizable English strings in source code, to decrease the time it takes to both read and write code that is internationalized.

- Constructor injection: learn it well, use it heavily. Avoid service locators. Avoid using DI frameworks in new projects (I could say a lot about this, but in short, the problem is that DI frameworks often change the way people write code in ways other than just encouraging dependency injection. If a framework were to encourage more constructor injection and fewer hard dependencies without affecting constructor parameter types, or encouraging more singletons, or affecting object lifetimes, it would be okay with me.)

- Spatial data structures for spatial data: quadtrees/octrees are simple and give reasonable performance; R* trees are more complex and slower to build but, when tuned properly, provide more accurate queries that scan less irrelevant data.

I also think we need programming language features that don’t exist in any/most popular languages yet:

- Unit inference (not merely unit checking) for units like metres, pixels, bytes, pixels per second squared, etc.

- Features for debugging visualization and testing built into the language (Bret Victor stuff)

- Features for compile-time metaprogramming

- Content-addressed VM code that can cross machine boundaries automatically

- Alias management and features to help libraries and interfaces evolve over time

- Improved genericity via parameterized namespaces/modules and specializations

- Dependent types (see Idris)

There is little funding for good tools, so the Future of Coding will have to wait. For now, a shout out to Julia, Nim, D, Nemerle and Haxe.

Comments